Just thought I'd leave a quick note to briefly explain what's going on with the blog. A slight redesign, to make the posts somewhat more pleasant to look at, and a barrage of new posts are the significant changes.

These new posts, of course, aren't new at all- they were produced as part of my Communication, Media and Culture Masters degree*. Now that I've completed my studies for that, I wanted to bring my posts into one central location. Partially so that I don't lose access to them when my University blog eventually expires, but also so that I can feel marginally better about my productivity when I look back on this year as a whole.

It is a year wherein which I have not published on this blog nearly as much as I'd have liked. That, perhaps, has mostly been down to pride. I am writing and envisioning content that I find myself too attached to for them to be published here. When I was using this blog primarily to rank the releases of new X-Men comic books, the low reach of the blog was fine. Ideal, really. But as I (and my posts) have become more ambitious, this low reach has grated, leaving me sitting on many completed pieces and letting a great deal more languish in rough drafts and states of half-completion. I'm having to ask myself a lot of questions with regard to what I actually want this blog to be and whether I'm comfortable with it just being a sort of content backlog.

Regardless, I'm hopeful that this post and refresh of the blog can signal a return to more consistent posting. Regrettably, I did say that the last time I wrote one of these personal updates as well. So, in applying a modicum of self-awareness, only time will tell.

*For the nosy, I found great academic success on my MA, achieving a Distinction and yielding a score on my dissertation that I had convinced myself was impossible. It was tough, it was stressful, I was losing hair and skin at hitherto unseen rates, but I made it to the end anyway.

Friday, 13 December 2019

Wednesday, 2 October 2019

Teen Wolves, Teen Zombies And Reappraising My Boyfriend's Back

The Universal Monster version of the werewolf seen in The Wolfman (1941) may not have been the first cinematic werewolf, but it certainly remains one of our foremost visions of lycanthropy on the silver screen. Or it did, until Michael J. Fox taped hair to basketball shorts and changed our view of the horror mainstay forever.

Teen Wolf (1985) was not the first film to greet the horror icons with humour and flippancy, as it was with drive-in theatre B-movies that first brought those horror tropes into a recognisable teen movie formulation. AIP films, such as I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957)/Frankenstein (1957) and Blood of Dracula (1957), were released to tap into the drive-in zeitgeist and brought the phenomenon of a monster hunting angsty teenagers to the exploitation scene.

The teenager, as a subculture, has been intrinsically tied to the development of modern capitalism, particularly being read as an emergent feature of America's post-war economic boom. These teen-horror films appealed to the newly economically liberated teenager subculture, sympathising particularly with the angst of their self-declaration. In I Was A Teenage Werewolf, it is the sentiments of teen peers which motivates the protagonist to seek psychiatric help, rather than any adult attempt in coercing him to 'adjust' (and it is the very adult institution of psychotherapy which inevitably betrays him). The film proved a success for this portrayal of teens who teens themselves could relate to, but the film was in a way quite cynical: it may have sympathised with the teenager, but it also saw the subculture as an unfortunate byproduct of the development of modernity.

In the conflict between the futurist scientist and the nostalgic suburbia that his experiment-gone-awry (the titular Werewolf) wreaks havoc on, the film professes a strong cautionary tale against progress: "It's not for man to interfere with the ways of God." The adolescence that the new teenager is exposed to is depicted as the unfortunate offspring of the modern society/depravity that emerged alongside America's new primacy as a global power.

This struggle with modernity and the conditions of hedonistic capitalism would persist for as long as viable alternatives made themselves clear: naturally, it was the era of Reaganism, neoliberalism and late capitalism that would transform I Was A Teenage Werewolf into Teen Wolf, a film where there is no longer an alternative, no deviant or subversive element left to be feared. As yesterday's fears dissipated, so too did yesterday's monsters.

Where I Was A Teenage Werewolf ends with its teen wolf shot dead, and a lament over man's hubris in interfering with the territory of God, Teen Wolf straight up transforms into a basketball film for its final fifteen minutes. This was the journey that the supernatural film had taken: from the indisputable, pre-modern fear of the supernatural in The Wolfman, to a more nebulous fear of a modern degenerative, delinquent tendency in I Was A Teenage Werewolf, culminating in Teen Wolf's post-modern absence of fear. The subversive element, the monster, is no longer to be feared, since it can so easily be subsumed into the normative order. Michael J. Fox's wolf form causes no existential crisis for his fellow students or for his community, rather they prefer the wolf to his human form. The wolf is cool, adorned on t-shirts and becomes the school's new mascot. Does this not perfectly mediate the way in which late-capitalism has proven to assimilate all counter-cultural forces into its hegemonic block?

And Teen Wolf was not the only Horror-Comedy to demonstrate this inefficacy of outdated myth. The unrepentantly silly and absurdist 1993 RomZomCom My Boyfriend's Back, fits nicely into this frame. This RomZomCom, a term attributed to and popularised by Edgar Wright's Shaun of the Dead (2004) simply meaning Romantic-Zombie-Comedy, is unlike much of its peers; there is no modicum of fear to be found in its depictions of zombieism. It rarely, if ever, feels like a film actually about zombies. There's no slow, intense walk of the newly awakened dead, nor the frenzy rush of infected runners, but rather a diffident, inoffensive teenager (who just so happens to have a craving for flesh, but who are we to judge?). As such, I find the film makes for much more interesting comparison when placed alongside a more optimistic film like Teen Wolf than to any other comedic zombie affair.

For one, it seems quaint and cheesy in the face of modern successes, like Warm Bodies (2013), which it seems to have much in common with, and Zombieland (2009), which deliver their humour without compromising their status as a clear zombie film. More than this though, My Boyfriend's Back, like Teen Wolf before it, utilises the classic genre trope as a universal sign of misunderstanding. Werewolves and zombies (and later, vampires and ogres) are the deviant sexuality, or the radical communist, who we used to fear before capitalism made it clear that it would not be toppled. We now instead freely embrace them as part of the cultural salad bowl.

The film is unique in just how deftly it delivers its absurd everyday as part of its eschewal of the classic horror trope. Johnny Dingle's return from the dead is only ever met with slight surprise, as if he had gotten out of school an hour early rather than emerged from the grave and each line of dialogue is lent a pitch perfect deadpan that stuns you into bewilderment; watch the film and tell me that it doesn't leave you speechless, mouth agape, as you wonder just how on earth this got made. It doesn't do this by being shocking, but by being so unshocking that you can't help but be bemused.

Whenever it seems like Johnny Dingle might face consequences for his cannibalistic tendencies, he is swiftly forgiven after a polite apology or a romantic declaration. As his longstanding crush falls increasingly and illogically further in love with a gradually decaying corpse, she fetishises his very undead quality to a point where you have to question whether their relationship as two living people could actually work out, since the living appear to be so much more dysfunctional than the dead.

Its dream sequences operate for the sake of a gag or two and little else, proving to us that there are no hidden, psychic demons haunting the film. Yet, the film itself nevertheless has an almost constant dreamlike quality- where the most peculiar of things may happen, yet they persist as if they are normal, everyday occurrences. For some inexplicable reason, the majority of the films exposition is done through comic book panel sequences. It is never made clear why! I have no idea why! But this film defies such mundane questions as 'why'?

Much like Teen Wolf, the horror trope is burrowed deep under quirk and a comedic, consumerist optimism; an optimism wherein which the features of the horror movie are neatly resolved by its conclusion. In the post-modern revisitation of horror icons and tropes, there is nothing to fear. The second chance at real life that Johnny Dingle receives in the film's happy Hollywood ending is a negation of any of the preceding zombie deviancy: not just in the film proper, but across the genre as a whole. Sorry for the misunderstanding, we used to be afraid of zombies, but we know better now.

My Boyfriend's Back may be an incredibly dated film, but it is also a film that seems strangely ahead of its time and in need of immediate reappraisal. Watching it is a genuine experience: it's vapid, yet deeply funny; it is speciously a black comedy, but without any blackness; it is plain and inoffensive, yet, at the same time, incredibly surreal. It's also perfect as a Halloween movie for people who are too easily spooked.

Panned at release and more or less forgotten by the majority of audiences, I can safely say that this is the only film I will be recommending to people for the foreseeable future.

Teen Wolf (1985) was not the first film to greet the horror icons with humour and flippancy, as it was with drive-in theatre B-movies that first brought those horror tropes into a recognisable teen movie formulation. AIP films, such as I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957)/Frankenstein (1957) and Blood of Dracula (1957), were released to tap into the drive-in zeitgeist and brought the phenomenon of a monster hunting angsty teenagers to the exploitation scene.

The teenager, as a subculture, has been intrinsically tied to the development of modern capitalism, particularly being read as an emergent feature of America's post-war economic boom. These teen-horror films appealed to the newly economically liberated teenager subculture, sympathising particularly with the angst of their self-declaration. In I Was A Teenage Werewolf, it is the sentiments of teen peers which motivates the protagonist to seek psychiatric help, rather than any adult attempt in coercing him to 'adjust' (and it is the very adult institution of psychotherapy which inevitably betrays him). The film proved a success for this portrayal of teens who teens themselves could relate to, but the film was in a way quite cynical: it may have sympathised with the teenager, but it also saw the subculture as an unfortunate byproduct of the development of modernity.

In the conflict between the futurist scientist and the nostalgic suburbia that his experiment-gone-awry (the titular Werewolf) wreaks havoc on, the film professes a strong cautionary tale against progress: "It's not for man to interfere with the ways of God." The adolescence that the new teenager is exposed to is depicted as the unfortunate offspring of the modern society/depravity that emerged alongside America's new primacy as a global power.

This struggle with modernity and the conditions of hedonistic capitalism would persist for as long as viable alternatives made themselves clear: naturally, it was the era of Reaganism, neoliberalism and late capitalism that would transform I Was A Teenage Werewolf into Teen Wolf, a film where there is no longer an alternative, no deviant or subversive element left to be feared. As yesterday's fears dissipated, so too did yesterday's monsters.

Where I Was A Teenage Werewolf ends with its teen wolf shot dead, and a lament over man's hubris in interfering with the territory of God, Teen Wolf straight up transforms into a basketball film for its final fifteen minutes. This was the journey that the supernatural film had taken: from the indisputable, pre-modern fear of the supernatural in The Wolfman, to a more nebulous fear of a modern degenerative, delinquent tendency in I Was A Teenage Werewolf, culminating in Teen Wolf's post-modern absence of fear. The subversive element, the monster, is no longer to be feared, since it can so easily be subsumed into the normative order. Michael J. Fox's wolf form causes no existential crisis for his fellow students or for his community, rather they prefer the wolf to his human form. The wolf is cool, adorned on t-shirts and becomes the school's new mascot. Does this not perfectly mediate the way in which late-capitalism has proven to assimilate all counter-cultural forces into its hegemonic block?

And Teen Wolf was not the only Horror-Comedy to demonstrate this inefficacy of outdated myth. The unrepentantly silly and absurdist 1993 RomZomCom My Boyfriend's Back, fits nicely into this frame. This RomZomCom, a term attributed to and popularised by Edgar Wright's Shaun of the Dead (2004) simply meaning Romantic-Zombie-Comedy, is unlike much of its peers; there is no modicum of fear to be found in its depictions of zombieism. It rarely, if ever, feels like a film actually about zombies. There's no slow, intense walk of the newly awakened dead, nor the frenzy rush of infected runners, but rather a diffident, inoffensive teenager (who just so happens to have a craving for flesh, but who are we to judge?). As such, I find the film makes for much more interesting comparison when placed alongside a more optimistic film like Teen Wolf than to any other comedic zombie affair.

For one, it seems quaint and cheesy in the face of modern successes, like Warm Bodies (2013), which it seems to have much in common with, and Zombieland (2009), which deliver their humour without compromising their status as a clear zombie film. More than this though, My Boyfriend's Back, like Teen Wolf before it, utilises the classic genre trope as a universal sign of misunderstanding. Werewolves and zombies (and later, vampires and ogres) are the deviant sexuality, or the radical communist, who we used to fear before capitalism made it clear that it would not be toppled. We now instead freely embrace them as part of the cultural salad bowl.

The film is unique in just how deftly it delivers its absurd everyday as part of its eschewal of the classic horror trope. Johnny Dingle's return from the dead is only ever met with slight surprise, as if he had gotten out of school an hour early rather than emerged from the grave and each line of dialogue is lent a pitch perfect deadpan that stuns you into bewilderment; watch the film and tell me that it doesn't leave you speechless, mouth agape, as you wonder just how on earth this got made. It doesn't do this by being shocking, but by being so unshocking that you can't help but be bemused.

Whenever it seems like Johnny Dingle might face consequences for his cannibalistic tendencies, he is swiftly forgiven after a polite apology or a romantic declaration. As his longstanding crush falls increasingly and illogically further in love with a gradually decaying corpse, she fetishises his very undead quality to a point where you have to question whether their relationship as two living people could actually work out, since the living appear to be so much more dysfunctional than the dead.

Its dream sequences operate for the sake of a gag or two and little else, proving to us that there are no hidden, psychic demons haunting the film. Yet, the film itself nevertheless has an almost constant dreamlike quality- where the most peculiar of things may happen, yet they persist as if they are normal, everyday occurrences. For some inexplicable reason, the majority of the films exposition is done through comic book panel sequences. It is never made clear why! I have no idea why! But this film defies such mundane questions as 'why'?

Much like Teen Wolf, the horror trope is burrowed deep under quirk and a comedic, consumerist optimism; an optimism wherein which the features of the horror movie are neatly resolved by its conclusion. In the post-modern revisitation of horror icons and tropes, there is nothing to fear. The second chance at real life that Johnny Dingle receives in the film's happy Hollywood ending is a negation of any of the preceding zombie deviancy: not just in the film proper, but across the genre as a whole. Sorry for the misunderstanding, we used to be afraid of zombies, but we know better now.

My Boyfriend's Back may be an incredibly dated film, but it is also a film that seems strangely ahead of its time and in need of immediate reappraisal. Watching it is a genuine experience: it's vapid, yet deeply funny; it is speciously a black comedy, but without any blackness; it is plain and inoffensive, yet, at the same time, incredibly surreal. It's also perfect as a Halloween movie for people who are too easily spooked.

Panned at release and more or less forgotten by the majority of audiences, I can safely say that this is the only film I will be recommending to people for the foreseeable future.

Tuesday, 12 February 2019

Post-Nuclear Utopia: The Fallout Franchise and Its Ultraconservative Appeal

Considering Bethesda's loud and proud anti-nazism marketing campaign for its alternate-history first-person shooter Wolfenstein 2, it's interesting to note that the fanbase of another of the company's major franchises, Fallout, is ripe with right-wing rhetoric, ultra-conservatism and, yes, fascism. That is, the same hyper-nationalist, white-supremacist fascism that was decried in the Wolfenstein 2 campaign. The Fallout game-franchise is, then, the backdrop for another round of the ongoing culture wars; the first step in unpacking the franchise's appeal to the ultraconservative is to isolate its origins and then to ask to what extent does Bethesda's own work account for this extremist fanbase.

For the unfamiliar, the Fallout franchise sets role-players loose into a retrofuturistic, post-apocalyptic America. Starting out in isometric form in 1997, the series would jump between developers and publishers until it was realised, in its current, recognisable form, as an extension of Bethesda Game Studios' first-person, open-world game design philosophy- a science-fiction counterpart to the Elder Scrolls' immersive fantasy experience. With the latest entry, Fallout 76, released on November 18th of last year, there has never been a more poignant time to imperil Fallout’s ultraconservative appeal.

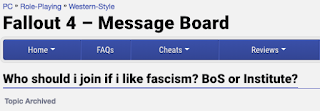

The franchise tells satirical narratives of the future, with the “76” in Fallout 76 referring not to 1976 but 2076, and these narratives are often satirising conservative politics and lifestyles; suggesting that all a conservative mindset can give to us is the apocalypse. When we question why the Fallout franchise can seem so accommodating to audience’s who would, on a surface level, appear opposed to the game’s, and its developer’s, expressed values, we can see a few potential answers staring back at us. The first is simple: gun fans like gunplay. On a ludological level, Fallout’s lone-wanderer-with-a-gun approach to game design resonates with a subgroup of gamers who have an active interest in firearms, along with small government political policy; the open world allowing the player to enjoy the fantasy of a nomadic, libertarian existence. Yet, this reading is painfully myopic, on account of the wider, cultural appeal of gunplay. Naturally, there is a strict role of guns in the formation of the modern conservative identity, but gunplay in games is enjoyed across a vast swathe of fan subgroups and, certainly, conservatives have no monopoly on firearm fanaticism. So we are obliged to look beyond this and, when we do, we can see that actual conservative spaces have been carved out within Fallout fan communities themselves. I assert that this particular fan space exists, not due to the text, but in spite of it.

In the case of the open world's inherent appeal to far-right gamers, we see a selective enjoyment indicative of the wider ironic detachment that characterises not just engagement with Fallout, but with engagement throughout the digital era. Whilst the conservative reads the lawless wasteland as a reflection of policy and an idealised storyworld, they can simultaneously detach themselves from the deviant sexualities and lifestyles that make themselves present in the game and which run counter to their worldview. This is prominent in conservative fan assembly around the term, “degenerate”, used by in-game characters (and game director Todd Howard) to deride unsavoury storyworld elements. Accommodated by the in-game factions and multiplicity of in-game ideology and identity, any gamer (not just the ultraconservative) can engage with every constituent element without feeling that any one has any meaning outside of its fictional habitat.

There’s a prevailing belief that one can engage, ironically, insincerely, with every element of the digital era and this has incubated the normalisation and legitimisation of increasingly reactionary viewpoints. On the alt-right, Dr. Alice Marwick has said that “irony allows people to strategically distance themselves from the very real commitment to white supremacist values that many of these forums have”, which particularly rears its head with Fallout’s beloved fascist faction, the Brotherhood of Steel. To engage, ironically, with Fallout is to engage unironically with its satire. This, in turn, accommodates an unironic, unironic engagement, as an (reactionary) audience can only then read Fallout sincerely. They can read the promise of post-nuclear freedom and renewed Americana as part of the franchise’s brand, disregarding any subversive affect its creators may have intended.

The dissonance between conservative engagement and a proposed satire of conservatism, then, actually matters little; intentionally or not, Fallout’s constant negotiation and renegotiation of meaning allowed the creation of a space that could be filled by the ultraconservative and the hypernationalist. This though begs the question, where did the right-wing elements come from to fill this space? What is it about the world of Fallout that is so appealing to them?

Retrofuturism, a term used to describe the utopian fantasies of the futures of yesteryear, is perhaps the crux of the question around Fallout’s conservatism. In retrofutures, we see again the science fiction iconography that went hand-in-hand with that era; for the 1950s this included jetpacks, flying cars, homes of tomorrow and so on. Remnants of Fallout’s retrofuture are seen scattered across the wasteland, the abandoned vaults with every Cold War styling and amenity are littered with “Mr. Handy” servant-robots (and even the aliens of the franchise are more reminiscent of Roswell and UFO fervour than any other sci-fi touchstone), but the post-war, post-apocalypse has little to offer in its longing for yesterday’s future. It is in specifically pre-war sections of the game (flashbacks, simulations and the ilk), which are not the franchise’s focal point, where the retrofuturistic conservatism shines through.

As each new entry to the franchise gives an obligatory return to the pre-war retrofuture of the 2070s, Bethesda Game Studios reiterates a prognostalgia, a sincere sadness for a future that never came to pass, which characterises the rest of the game. This is seen in Fallout 3’s opening, where the main protagonist grows up in a time-capsule-like vault, and its sequel Fallout 4’s also, where the main character was present in the nostalgic pre-war era. Whilst other studios working on the IP forsook such direct flashbacks, Bethesda Game Studios weaves this sombreness, this regretful tone throughout the experiences of both games. This gives way to the accommodation of what I call the myth of Fallout. Rather than a legendary myth, this is a myth of the Barthesian sense, where in which the nuclear fallout depicted in the game is not the end of the world, but instead a rebirth of conservative politics. The promise of this myth is that, after the bombs fall, the nostalgic, conservative past will be returned to us, imbued with new vigour to pursue the same American ideals and dreams as ever.

No aspect of the game series encapsulates this renewed, militant Americanism like Liberty Prime; a pastiche “Iron Giant” who foregoes anti-militarism and anti-nuclear sentiment for an uncritical adulation of “democracy” and American capitalism. Liberty Prime, appearing in Fallout 3 and Fallout 4, is shown as an imposing, if retrograde, American military marvel. Like any good American soldier, he is deeply patriotic, spouting anti-communist slogans and propaganda akin to what may have been heard during the Cold War. It’s even wrong to call the giant robot an instance of nuclear deterrence, as he hurls miniaturised atom bombs at his enemies. As metallic shouts of "Death is a preferable alternative to communism," ring through the battlefield, the robot exists as the zenith of Fallout’s retrofuture; a technological marvel constrained by the hatred and prejudice of its time of creation. It is, then, noteworthy how beloved the automaton became. Not as a criticism of myopic Cold War militarism, but as a sincere, bastion of libertarian values. Even now he is a touchstone for the reactionary, the ultimate vindication that their reading of Fallout is the right one. Take a look at some fan commentary from a YouTube compilation of Liberty Prime quotes:

Not only is the line between fiction and reality blurred, with desires to see the giant robot crush the enemies of fascism, but so is the line between satire and sincerity. In the unironic, uncritical responses to characters such as Liberty Prime and storyworlds like Fallout, we can see that the transformation of democracy from a rule of government to a set of intrinsically American values and beliefs has abetted the anti-democrat to take the violent pursuit of "democracy" into their own identity. As Liberty Prime would declare, "Democracy is non-negotiable," and now is a broader referent, one that encapsulates the American project as a whole. Fascism may be anti-conservative, in that it doesn't seek a return to the past but a rebirth based on past iconography, but it is that very distinction that attracts the ultraconservative and the fascist alike. Fallout's promise of a nuclear apocalypse which ushers in traditional values exists as both a return to Cold War Americana and a rebirth of the nation state, allowing a ground zero from which fascistic imagination can play.

The idealised past (that of course never existed) is revisited, in Fallout, in a form of perverse utopia. The ultraconservatives find, in Fallout's wastelands, a utopian world, free from the constraints and responsibilities of our present one. We can see this idealised past again, throughout the franchise’s Americana aesthetic. Particularly, the music creates a strong sense of nostalgic longing, but not for the in-universe character. These songs, famous jaunty pop tracks from yesteryear, are nostalgic for a prior state of the world. A world promised to the ultraconservative player, after the bombs fall. With Fallout 76's promotional material, merging The Ink Spots’ "I Don't Want To Set The World On Fire" (popularised by Fallout 3) with John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads", we can see that the anachronism (Denver's song was released in 1971, long after Fallout's 50s point of reference) means nothing. The music is not representative of the world's past, but rather our world's past which is, in turn, this world's present. The themes and tone of Denver's song are no coincidence either; a classic country song ushering you back to a vague notion of home; communicating the idea that the world offered in Fallout is a home, of sorts. One which appears as a safe space for the moral workings and philosophical lenses that no longer seem to have such a home.

As opposed to most retrofuturistic narratives, the core of the Fallout franchise actually affords us an element of subversion, threatening to turn the conservativeness inherent to retro on its head. We are brought into a storyworld where every American imagineer had their dreams fulfilled, where conservative social values (like the nuclear family and white suburbia) remained unchallenged, and yet this can do nothing but yield armageddon. The question of why Fallout’s future is so 50s referential, in particular, has been bounced around for a while, but I think I finally have the answer. The retrofuture isn’t merely a representative of an uncritical, happy time that can be universally enjoyed before the horrors of nuclear war takes it away; the retrofuture tracks a specific narrative, one where social values don’t accelerate to keep up with technological progress. It condemns retrofuturistic ideals specifically by having the outcome of their implementation being a nigh-total apocalypse. Why the 50s? Why invoke the imagery, language and iconography of Cold War? Simply, because it can be nowhere else. The unabashed Space Age optimism running alongside profound domestic and international anxieties in Cold War America is a duality that can not be undersold. To turn the retrofuture against itself, Fallout pushes this duality to its final, deadly conclusion.

Fallout, though, can never seem to outrun its sincere readers and perhaps this is because its very nature as a video game denies any definitive communication between authorial intent and an audience reading. This is, of course, only exacerbated by situating it in the open-world, role-playing genre. It may be the case that this openness is going too far for a developer to manage. You cannot simultaneously offer freedom of choice and effectively communicate a singular message or cohesive world.

So, to some, Fallout's wasteland is a utopian dream of rebirth, tapping into the spirit of manifest destiny. America, after nuclear war, can once again become the new frontier, pursuing a patriotic endeavour for a future characterised by its past. Whilst I’ve expressed that this is a counter-reading of the text, it is worthwhile to examine the culpability of Bethesda in the curation of this perspective. With Fallout 76's recent launch, a game that promised to transition the series from retrofuturistic satire to post-apocalyptic fun with friends, we cannot just assume that Bethesda has experienced a “death of the author” moment and lost all control over their text. Rather the commitment to apolitical, open design has cultivated this ambiguity of meaning in order to fulfil its escapist promise and to ensure a cross-political appeal.

Bethesda operates within a political vacuum, arbitrarily flitting between political statements so as to best sell the latest product. Wolfenstein played into antifa, "bash the fash", imagery in a sensational, timely campaign, yet The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (and, as I’ve laid out, the Fallout franchise) has intentionally curated appeals to the far-right, ultraconservative. White nationalism and imperialism are a window dressing Bethesda Game Studios often deploys uncritically, leading to a perennial contradiction between the proposed corporate ethos and the actual corporate product. Game franchises such as The Elder Scrolls and Fallout, which promote player choice and determination, simultaneously depoliticise and construct an in-game political sphere from which the player can act out political conflict with a sense of ironic detachment. There is no right-wing or left-wing, but Stormcloak and Imperial or Brotherhood of Steel and Railroad.

The trailer for Fallout 76 has currently amassed over 32 million views on YouTube and moves the subject of the franchise away from the conservative satire of previous entries, declaring in no uncertain terms that this latest franchise entry is about rebuilding America in the image of its idealised past. It seems that, on some level, Bethesda are embracing their nostalgic, hyper-nationalist base. There are, of course, always extremists willing to take counter-readings of popular texts. There is always a reactionary community that will contort and contrive to find representation or legitimisation from popular media, seen ever since the internet's very first hate sites. This, however, should not absolve the product that makes such entities feel welcome. At the very least, they should be interrogated. Fascism makes alliances and, in American fascism, it makes alliances with the traditionalist, the nationalist, the militarist and finds financial backing in big business and wealthy elites. For a long time, the perception of gaming as juvenile has absolved this particular industry of meaningful criticism. But, when we can see the conservative coalition forming around media products, we should not take that as an inherent reality of the form.

For the unfamiliar, the Fallout franchise sets role-players loose into a retrofuturistic, post-apocalyptic America. Starting out in isometric form in 1997, the series would jump between developers and publishers until it was realised, in its current, recognisable form, as an extension of Bethesda Game Studios' first-person, open-world game design philosophy- a science-fiction counterpart to the Elder Scrolls' immersive fantasy experience. With the latest entry, Fallout 76, released on November 18th of last year, there has never been a more poignant time to imperil Fallout’s ultraconservative appeal.

The franchise tells satirical narratives of the future, with the “76” in Fallout 76 referring not to 1976 but 2076, and these narratives are often satirising conservative politics and lifestyles; suggesting that all a conservative mindset can give to us is the apocalypse. When we question why the Fallout franchise can seem so accommodating to audience’s who would, on a surface level, appear opposed to the game’s, and its developer’s, expressed values, we can see a few potential answers staring back at us. The first is simple: gun fans like gunplay. On a ludological level, Fallout’s lone-wanderer-with-a-gun approach to game design resonates with a subgroup of gamers who have an active interest in firearms, along with small government political policy; the open world allowing the player to enjoy the fantasy of a nomadic, libertarian existence. Yet, this reading is painfully myopic, on account of the wider, cultural appeal of gunplay. Naturally, there is a strict role of guns in the formation of the modern conservative identity, but gunplay in games is enjoyed across a vast swathe of fan subgroups and, certainly, conservatives have no monopoly on firearm fanaticism. So we are obliged to look beyond this and, when we do, we can see that actual conservative spaces have been carved out within Fallout fan communities themselves. I assert that this particular fan space exists, not due to the text, but in spite of it.

In the case of the open world's inherent appeal to far-right gamers, we see a selective enjoyment indicative of the wider ironic detachment that characterises not just engagement with Fallout, but with engagement throughout the digital era. Whilst the conservative reads the lawless wasteland as a reflection of policy and an idealised storyworld, they can simultaneously detach themselves from the deviant sexualities and lifestyles that make themselves present in the game and which run counter to their worldview. This is prominent in conservative fan assembly around the term, “degenerate”, used by in-game characters (and game director Todd Howard) to deride unsavoury storyworld elements. Accommodated by the in-game factions and multiplicity of in-game ideology and identity, any gamer (not just the ultraconservative) can engage with every constituent element without feeling that any one has any meaning outside of its fictional habitat.

There’s a prevailing belief that one can engage, ironically, insincerely, with every element of the digital era and this has incubated the normalisation and legitimisation of increasingly reactionary viewpoints. On the alt-right, Dr. Alice Marwick has said that “irony allows people to strategically distance themselves from the very real commitment to white supremacist values that many of these forums have”, which particularly rears its head with Fallout’s beloved fascist faction, the Brotherhood of Steel. To engage, ironically, with Fallout is to engage unironically with its satire. This, in turn, accommodates an unironic, unironic engagement, as an (reactionary) audience can only then read Fallout sincerely. They can read the promise of post-nuclear freedom and renewed Americana as part of the franchise’s brand, disregarding any subversive affect its creators may have intended.

The dissonance between conservative engagement and a proposed satire of conservatism, then, actually matters little; intentionally or not, Fallout’s constant negotiation and renegotiation of meaning allowed the creation of a space that could be filled by the ultraconservative and the hypernationalist. This though begs the question, where did the right-wing elements come from to fill this space? What is it about the world of Fallout that is so appealing to them?

Retrofuturism, a term used to describe the utopian fantasies of the futures of yesteryear, is perhaps the crux of the question around Fallout’s conservatism. In retrofutures, we see again the science fiction iconography that went hand-in-hand with that era; for the 1950s this included jetpacks, flying cars, homes of tomorrow and so on. Remnants of Fallout’s retrofuture are seen scattered across the wasteland, the abandoned vaults with every Cold War styling and amenity are littered with “Mr. Handy” servant-robots (and even the aliens of the franchise are more reminiscent of Roswell and UFO fervour than any other sci-fi touchstone), but the post-war, post-apocalypse has little to offer in its longing for yesterday’s future. It is in specifically pre-war sections of the game (flashbacks, simulations and the ilk), which are not the franchise’s focal point, where the retrofuturistic conservatism shines through.

As each new entry to the franchise gives an obligatory return to the pre-war retrofuture of the 2070s, Bethesda Game Studios reiterates a prognostalgia, a sincere sadness for a future that never came to pass, which characterises the rest of the game. This is seen in Fallout 3’s opening, where the main protagonist grows up in a time-capsule-like vault, and its sequel Fallout 4’s also, where the main character was present in the nostalgic pre-war era. Whilst other studios working on the IP forsook such direct flashbacks, Bethesda Game Studios weaves this sombreness, this regretful tone throughout the experiences of both games. This gives way to the accommodation of what I call the myth of Fallout. Rather than a legendary myth, this is a myth of the Barthesian sense, where in which the nuclear fallout depicted in the game is not the end of the world, but instead a rebirth of conservative politics. The promise of this myth is that, after the bombs fall, the nostalgic, conservative past will be returned to us, imbued with new vigour to pursue the same American ideals and dreams as ever.

No aspect of the game series encapsulates this renewed, militant Americanism like Liberty Prime; a pastiche “Iron Giant” who foregoes anti-militarism and anti-nuclear sentiment for an uncritical adulation of “democracy” and American capitalism. Liberty Prime, appearing in Fallout 3 and Fallout 4, is shown as an imposing, if retrograde, American military marvel. Like any good American soldier, he is deeply patriotic, spouting anti-communist slogans and propaganda akin to what may have been heard during the Cold War. It’s even wrong to call the giant robot an instance of nuclear deterrence, as he hurls miniaturised atom bombs at his enemies. As metallic shouts of "Death is a preferable alternative to communism," ring through the battlefield, the robot exists as the zenith of Fallout’s retrofuture; a technological marvel constrained by the hatred and prejudice of its time of creation. It is, then, noteworthy how beloved the automaton became. Not as a criticism of myopic Cold War militarism, but as a sincere, bastion of libertarian values. Even now he is a touchstone for the reactionary, the ultimate vindication that their reading of Fallout is the right one. Take a look at some fan commentary from a YouTube compilation of Liberty Prime quotes:

Not only is the line between fiction and reality blurred, with desires to see the giant robot crush the enemies of fascism, but so is the line between satire and sincerity. In the unironic, uncritical responses to characters such as Liberty Prime and storyworlds like Fallout, we can see that the transformation of democracy from a rule of government to a set of intrinsically American values and beliefs has abetted the anti-democrat to take the violent pursuit of "democracy" into their own identity. As Liberty Prime would declare, "Democracy is non-negotiable," and now is a broader referent, one that encapsulates the American project as a whole. Fascism may be anti-conservative, in that it doesn't seek a return to the past but a rebirth based on past iconography, but it is that very distinction that attracts the ultraconservative and the fascist alike. Fallout's promise of a nuclear apocalypse which ushers in traditional values exists as both a return to Cold War Americana and a rebirth of the nation state, allowing a ground zero from which fascistic imagination can play.

The idealised past (that of course never existed) is revisited, in Fallout, in a form of perverse utopia. The ultraconservatives find, in Fallout's wastelands, a utopian world, free from the constraints and responsibilities of our present one. We can see this idealised past again, throughout the franchise’s Americana aesthetic. Particularly, the music creates a strong sense of nostalgic longing, but not for the in-universe character. These songs, famous jaunty pop tracks from yesteryear, are nostalgic for a prior state of the world. A world promised to the ultraconservative player, after the bombs fall. With Fallout 76's promotional material, merging The Ink Spots’ "I Don't Want To Set The World On Fire" (popularised by Fallout 3) with John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads", we can see that the anachronism (Denver's song was released in 1971, long after Fallout's 50s point of reference) means nothing. The music is not representative of the world's past, but rather our world's past which is, in turn, this world's present. The themes and tone of Denver's song are no coincidence either; a classic country song ushering you back to a vague notion of home; communicating the idea that the world offered in Fallout is a home, of sorts. One which appears as a safe space for the moral workings and philosophical lenses that no longer seem to have such a home.

As opposed to most retrofuturistic narratives, the core of the Fallout franchise actually affords us an element of subversion, threatening to turn the conservativeness inherent to retro on its head. We are brought into a storyworld where every American imagineer had their dreams fulfilled, where conservative social values (like the nuclear family and white suburbia) remained unchallenged, and yet this can do nothing but yield armageddon. The question of why Fallout’s future is so 50s referential, in particular, has been bounced around for a while, but I think I finally have the answer. The retrofuture isn’t merely a representative of an uncritical, happy time that can be universally enjoyed before the horrors of nuclear war takes it away; the retrofuture tracks a specific narrative, one where social values don’t accelerate to keep up with technological progress. It condemns retrofuturistic ideals specifically by having the outcome of their implementation being a nigh-total apocalypse. Why the 50s? Why invoke the imagery, language and iconography of Cold War? Simply, because it can be nowhere else. The unabashed Space Age optimism running alongside profound domestic and international anxieties in Cold War America is a duality that can not be undersold. To turn the retrofuture against itself, Fallout pushes this duality to its final, deadly conclusion.

Fallout, though, can never seem to outrun its sincere readers and perhaps this is because its very nature as a video game denies any definitive communication between authorial intent and an audience reading. This is, of course, only exacerbated by situating it in the open-world, role-playing genre. It may be the case that this openness is going too far for a developer to manage. You cannot simultaneously offer freedom of choice and effectively communicate a singular message or cohesive world.

So, to some, Fallout's wasteland is a utopian dream of rebirth, tapping into the spirit of manifest destiny. America, after nuclear war, can once again become the new frontier, pursuing a patriotic endeavour for a future characterised by its past. Whilst I’ve expressed that this is a counter-reading of the text, it is worthwhile to examine the culpability of Bethesda in the curation of this perspective. With Fallout 76's recent launch, a game that promised to transition the series from retrofuturistic satire to post-apocalyptic fun with friends, we cannot just assume that Bethesda has experienced a “death of the author” moment and lost all control over their text. Rather the commitment to apolitical, open design has cultivated this ambiguity of meaning in order to fulfil its escapist promise and to ensure a cross-political appeal.

Bethesda operates within a political vacuum, arbitrarily flitting between political statements so as to best sell the latest product. Wolfenstein played into antifa, "bash the fash", imagery in a sensational, timely campaign, yet The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (and, as I’ve laid out, the Fallout franchise) has intentionally curated appeals to the far-right, ultraconservative. White nationalism and imperialism are a window dressing Bethesda Game Studios often deploys uncritically, leading to a perennial contradiction between the proposed corporate ethos and the actual corporate product. Game franchises such as The Elder Scrolls and Fallout, which promote player choice and determination, simultaneously depoliticise and construct an in-game political sphere from which the player can act out political conflict with a sense of ironic detachment. There is no right-wing or left-wing, but Stormcloak and Imperial or Brotherhood of Steel and Railroad.

The trailer for Fallout 76 has currently amassed over 32 million views on YouTube and moves the subject of the franchise away from the conservative satire of previous entries, declaring in no uncertain terms that this latest franchise entry is about rebuilding America in the image of its idealised past. It seems that, on some level, Bethesda are embracing their nostalgic, hyper-nationalist base. There are, of course, always extremists willing to take counter-readings of popular texts. There is always a reactionary community that will contort and contrive to find representation or legitimisation from popular media, seen ever since the internet's very first hate sites. This, however, should not absolve the product that makes such entities feel welcome. At the very least, they should be interrogated. Fascism makes alliances and, in American fascism, it makes alliances with the traditionalist, the nationalist, the militarist and finds financial backing in big business and wealthy elites. For a long time, the perception of gaming as juvenile has absolved this particular industry of meaningful criticism. But, when we can see the conservative coalition forming around media products, we should not take that as an inherent reality of the form.

Friday, 1 February 2019

Fanfiction and "Feminizing" My Media Prosumption

After a not-so-restful Winter break and a severely stressful deadline season, my recent piece on The Simpsons has signalled (somewhat) my return to posting incessant nonsense. Over that Winter break though, I managed to produce something I have very conflicting opinions about: my first ever piece of fanfiction. I'm, of course, familiar with Ebony Dark'ness Dementia Raven Way, but this was really my first sincere engagement with fanfiction. It was a part of a wider project, one that I want to take the time to discuss a little: my personal attempt to disrupt the ways I engage with texts as a fan.

Prompting this is the increasingly widespread sentiment that women, in fan communities, often have to assimilate to male-dominated paradigms and spaces. This is the idea that women, in entry to fandom, are not only changing the products they consume (transitioning to needlessly male-dominated franchises and genres, such as Sci-Fi or Superhero, from the likewise needlessly female-dominated franchises, such as Romance stories or Young Adult fiction), but the way they produce and give back to fan communities. Engaging with this idea as a male prosumer (producer/consumer) turned into a project where I've sought to perform the inverse. Where women are expected to transition from feminine space to masculine ones, I, as a man, would transition from masculine to feminine. The prime avenue for this has been in finally exploring the world of fanfiction, no longer disregarding it as a petulant, juvenile thing (an outdated sentiment held over from my experiences as a teenager engaged with fandom).

You can read the fanfiction here. Frankly, the quality of the story isn't something I'm particularly happy with. I find capturing the voice of someone else's characters remains incredibly difficult, regardless of how much time you've spent immersed in the fictions they're from. It's kind of a punishing sensation, as it never really reflects the research you've done to finish your writing and, in that sense, it's far more of a challenging instance of fanwork than what is purported as its masculine equivalent: the fan theory. Where fanfiction creates new stories, the fan theory intends to further explain or develop existing stories; yet, the word "theory" belies its inherently fictional nature. Whilst these theories are derived from the existing fiction the fan is engaged with, these fictional facts, truths and histories experience much the same kind of mutation as the characters of fanfictions do.

This isn't to say that either fiction or theory are necessarily masculine/feminine pursuits, but rather this is meant to elucidate the gatekeeping that occurs around the conventionally masculine spaces of fandom compared to the relatively more open feminine spaces. Fanfiction community is certainly a (cyber)space which emerged in response to the gendered politics of masculine fandom; the splits of these communities can be traced back to the ideas of geek culture as a sphere inherently for men. Can we not say that the fan theory, as masculine counter-part to the feminine fanfiction, is rooted in this gatekeeping? It abandons character and emotional intuition for methodical, in-depth knowledge of lore, demanding a almost ideological purity from its participants. The discord between supposed feminine and masculine fan spaces can be seen through the response to Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Particularly, in its final duel between (female) protagonist Rey and antagonist Kylo Ren.

(On Star Wars, is it not telling that the male response to their disappointment in Star Wars: The Last Jedi was to seek funding for someone else to produce their fanfiction ideas? There is such a disdain for feminine elements of fandom, both in its texts and its practices, that the majority of male fans can't even conceive of engaging with the conventionally feminine spaces.)

So, in my work, one thing I was really keen on doing was to move my engagement away from feats, power levels and so on, instead taking a look at emotional, character-driven conflict. I felt it would be counter-intuitive to engage with the fanfiction space and not with its sentiment. Keeping in mind that I don't think I did a particularly good enough job on it, my fanfiction was primarily concerned with what happens to someone's relationship when their preferred method of communication is taken away from them (in that I was writing in response to a superhero text, that method was telepathy).

Something I'm particularly interested in is what I call Critical Fanfiction. Simply, fanfiction that works to change elements of its mothership text to pursue a author/audience resolution. On one level, sure, this is a pretty arbitrary and meaningless term. Most fanfiction serves as this: a fan may prefer Lord of the Rings if it was set in a coffee shop or if it had a crossover with the Game of Thrones franchise, for example. But there are deeper questions to be asked when the fanfiction goes beyond a fan's wish fulfilment and starts to resemble a form of fictionalised criticism of the text. When does slash fiction cease to be fantasy and morph into a critique of the author's heteronormative writing? When does the submissive reader morph into a critical one, and what does it say that this transformation occurs within the immersion of the text itself? A personal favourite discovery of mine has been the Harry Potter Becomes A Communist fanwork; is this not valuable as a response to the politics of J.K. Rowling and the ideas she injected into the franchise?

In our era of ubiquitous communication, this is reaching new, more torrid depths. Where the author once responded to fanfiction with hefty lawsuits, the author is now responding directly to criticism through social media, seeking to retroactively assert their own authorial primacy. Fanfiction is, I think, then a useful tool not merely to interrogate and view fan cultures and communities, but as an act with merit itself. It is caught in battles both between reader and author and between segmented communities. Moving between these masculine/feminine communities and being critical of the distinctions and separations can not only help transform fandom away from its toxicity, but could also see the return of fan praxis. Not the fan activism that seeks to pressure production companies into providing them with more content to consume, but an actual grassroots reclamation of intellectual labour and property. This, and fan studies/IP in general, is something I want to write about in more depth at a later date.

Briefly, I want to return to my place in this process though (and I do consider it an ongoing process). To the end of disrupting my gendered media consumption/participation, tonight I intend to finally sit down and watch Twilight. From its release and time in the spotlight to its eventual fading away, I participated in the vitriolic male response that held it in such disdain without ever seeing it. I think it's wrong to suggest this solely came from a disregard for media texts intended for young women (certainly, women themselves partook in Twilight-bashing), but I also think it's wrong to overlook the significance of it (Lindsay Ellis did a great video on this that you can see here). Do I expect to like it? Not particularly. I'm a long-time Buffyverse fan and have a very specific imagination when it comes to vampires because of that. Nevertheless, it will be valuable to finally form my own organic opinion about it and be able to move somewhat away from the reactionary frameworks that have oft clouded my perspectives as someone who at least pretends to engage with media critically.

Prompting this is the increasingly widespread sentiment that women, in fan communities, often have to assimilate to male-dominated paradigms and spaces. This is the idea that women, in entry to fandom, are not only changing the products they consume (transitioning to needlessly male-dominated franchises and genres, such as Sci-Fi or Superhero, from the likewise needlessly female-dominated franchises, such as Romance stories or Young Adult fiction), but the way they produce and give back to fan communities. Engaging with this idea as a male prosumer (producer/consumer) turned into a project where I've sought to perform the inverse. Where women are expected to transition from feminine space to masculine ones, I, as a man, would transition from masculine to feminine. The prime avenue for this has been in finally exploring the world of fanfiction, no longer disregarding it as a petulant, juvenile thing (an outdated sentiment held over from my experiences as a teenager engaged with fandom).

You can read the fanfiction here. Frankly, the quality of the story isn't something I'm particularly happy with. I find capturing the voice of someone else's characters remains incredibly difficult, regardless of how much time you've spent immersed in the fictions they're from. It's kind of a punishing sensation, as it never really reflects the research you've done to finish your writing and, in that sense, it's far more of a challenging instance of fanwork than what is purported as its masculine equivalent: the fan theory. Where fanfiction creates new stories, the fan theory intends to further explain or develop existing stories; yet, the word "theory" belies its inherently fictional nature. Whilst these theories are derived from the existing fiction the fan is engaged with, these fictional facts, truths and histories experience much the same kind of mutation as the characters of fanfictions do.

This isn't to say that either fiction or theory are necessarily masculine/feminine pursuits, but rather this is meant to elucidate the gatekeeping that occurs around the conventionally masculine spaces of fandom compared to the relatively more open feminine spaces. Fanfiction community is certainly a (cyber)space which emerged in response to the gendered politics of masculine fandom; the splits of these communities can be traced back to the ideas of geek culture as a sphere inherently for men. Can we not say that the fan theory, as masculine counter-part to the feminine fanfiction, is rooted in this gatekeeping? It abandons character and emotional intuition for methodical, in-depth knowledge of lore, demanding a almost ideological purity from its participants. The discord between supposed feminine and masculine fan spaces can be seen through the response to Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Particularly, in its final duel between (female) protagonist Rey and antagonist Kylo Ren.

The comments section of that video is representative of the majority male response. Masculine fandom seems generally more focused on the laws of the storyworld: Kylo receives training in the magic system, this training allows for better skills with the lightsaber and, therefore, he should not lose to the comparatively untrained Rey. The response of feminine fandom was different, generally more focused on character: Kylo is at a disadvantage in the duel due to some post-patricide emotional turmoil and, therefore, has to lose to the comparatively focused, survivor Rey.

(On Star Wars, is it not telling that the male response to their disappointment in Star Wars: The Last Jedi was to seek funding for someone else to produce their fanfiction ideas? There is such a disdain for feminine elements of fandom, both in its texts and its practices, that the majority of male fans can't even conceive of engaging with the conventionally feminine spaces.)

So, in my work, one thing I was really keen on doing was to move my engagement away from feats, power levels and so on, instead taking a look at emotional, character-driven conflict. I felt it would be counter-intuitive to engage with the fanfiction space and not with its sentiment. Keeping in mind that I don't think I did a particularly good enough job on it, my fanfiction was primarily concerned with what happens to someone's relationship when their preferred method of communication is taken away from them (in that I was writing in response to a superhero text, that method was telepathy).

Something I'm particularly interested in is what I call Critical Fanfiction. Simply, fanfiction that works to change elements of its mothership text to pursue a author/audience resolution. On one level, sure, this is a pretty arbitrary and meaningless term. Most fanfiction serves as this: a fan may prefer Lord of the Rings if it was set in a coffee shop or if it had a crossover with the Game of Thrones franchise, for example. But there are deeper questions to be asked when the fanfiction goes beyond a fan's wish fulfilment and starts to resemble a form of fictionalised criticism of the text. When does slash fiction cease to be fantasy and morph into a critique of the author's heteronormative writing? When does the submissive reader morph into a critical one, and what does it say that this transformation occurs within the immersion of the text itself? A personal favourite discovery of mine has been the Harry Potter Becomes A Communist fanwork; is this not valuable as a response to the politics of J.K. Rowling and the ideas she injected into the franchise?

In our era of ubiquitous communication, this is reaching new, more torrid depths. Where the author once responded to fanfiction with hefty lawsuits, the author is now responding directly to criticism through social media, seeking to retroactively assert their own authorial primacy. Fanfiction is, I think, then a useful tool not merely to interrogate and view fan cultures and communities, but as an act with merit itself. It is caught in battles both between reader and author and between segmented communities. Moving between these masculine/feminine communities and being critical of the distinctions and separations can not only help transform fandom away from its toxicity, but could also see the return of fan praxis. Not the fan activism that seeks to pressure production companies into providing them with more content to consume, but an actual grassroots reclamation of intellectual labour and property. This, and fan studies/IP in general, is something I want to write about in more depth at a later date.

Briefly, I want to return to my place in this process though (and I do consider it an ongoing process). To the end of disrupting my gendered media consumption/participation, tonight I intend to finally sit down and watch Twilight. From its release and time in the spotlight to its eventual fading away, I participated in the vitriolic male response that held it in such disdain without ever seeing it. I think it's wrong to suggest this solely came from a disregard for media texts intended for young women (certainly, women themselves partook in Twilight-bashing), but I also think it's wrong to overlook the significance of it (Lindsay Ellis did a great video on this that you can see here). Do I expect to like it? Not particularly. I'm a long-time Buffyverse fan and have a very specific imagination when it comes to vampires because of that. Nevertheless, it will be valuable to finally form my own organic opinion about it and be able to move somewhat away from the reactionary frameworks that have oft clouded my perspectives as someone who at least pretends to engage with media critically.

Sunday, 20 January 2019

"Homer Loves Mindy": Desire At A Distance In "The Last Temptation of Homer"

Keeping in the spirit of working through heady, philosophical topics through episodes of The Simpsons, I want to analyse the fifth episode of season nine, "The Last Temptation of Homer" through Lacanian desire. The character of Mindy Simmons, a new employee at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant (voiced by Michelle Pfeiffer), performs as such desire for Homer; threatening to disrupt his model nuclear family and his marriage with Marge. Since Lacan's writings on desire is quite a hefty topic and I envision this post to be on the shorter side, I want to look particularly at how Mindy, as the object of Homer's desire, exhibits Lacan's objet petit a.

Whilst the episode's B-Plot sees Bart transition from cool kid to bullied nerd because of some over-zealous private practitioners, the A-Plot of "The Last Temptation of Homer" launches from a safety mishap in the Nuclear Plant. This inciting incident, caused by a masculine disregard for safety protocol, characterises working at the plant as a sort of 'Men's Club'; setting the stage for Mindy Simmon's hiring and her intrusion on the masculine space. Homer, Lenny and Carl gather to lament their incoming castration, fearing that the arrival of a singular female worker will so totally disrupt their workplace atmosphere that certain masculine freedoms will be removed from them (be it taking off their pants, spitting on the floor or peeing in the water fountain). That male anxiety is soon abetted by her seamless integration into the workplace, but whilst the rest of his co-workers move on quick from this new element, Homer is smitten. For him, his encounter with Mindy is a moment of pure desire upon first sight and it is accompanied by humorous hallucinations.

Importantly, the objet petit a does not actually exist. This is why when we finally attain what we desire it loses the metaphysical, theological quality, the objet petit a, which made what we desired desirable in the first place. Homer's hallucinations represent the fantastical excess of the objet petit a: his first feelings of desire towards Mindy are not grounded in material reality, but are rather concerned with such untraceable, intangible qualities.

Later in the episode, an interjecting dream sequence depicts Homer's Guardian Angel (who takes the form of Colonel Klink from Hogan's Heroes) showing the difference between the world where he stays with Marge and the world where he instead pursues a relationship with Mindy. Rather than this being a undesirable world though, it is quite the opposite. Not only are Homer and Mindy together, rich and happy, but Marge is the President of the United States, and her "approval rate is soaring". Here we see Homer's unconscious fantasy, that his affair would not only bring him a selfish, short-term happiness, but long-term happiness for himself, Mindy and Marge. But it is a fantasy of which there must be no attempt at realisation. Homer's desire for Mindy is based on the idea that his life, and that lives around him, would improve. To bring that to reality would only expose his desire as a farce, as reality can never live up to the fantasy.

One of the great strengths of this episode is how Mindy is never shown to be some kind of disruptive, evil woman, a seductress with the explicit aim of destroying the nuclear family; she's given a nice bit of humanity. Meanwhile Marge has very little presence in the episode and even in the dream sequence exposing her potential, alternate life as President, she's only heard from off-screen. Unlike an episode like "Colonel Homer" (S3E20), where a conflict between Homer/Marge is clearly apparent, the story here is not a story about how awful Homer's life is and how he needs an outlet to assuage his mid-life crisis, but rather a story that is concerned with those tumultuous, sudden moments of desire that simultaneously manage to feel essential to our being and completely alien from us.

In Lacan's formulation, the act of desire is not a desire for just one thing (be it a person, food or whatever item you may desire), but is always a desire for desire itself. It's a wholesome sight when Homer returns to Marge at the episode's end and the relief an audience feels is made all the more tangible by how close it seemed Homer had come to pursuing a life with Mindy, instead of persisting with his marriage. Yet, can we not say that this was actually the true calamity? In that, were he to pursue his relationship with Mindy, he would realise she lacks that objet petit a and would realise that his fantasy did not exist in reality. That he returned to Marge has meant that, whilst he ostensibly loves his wife, he has also liberated himself to fantasise about Mindy ad infinitum. In this sense, Homer doesn't want what he thinks he wants, rather he wants to sustain the very act of wanting. By returning to Marge, he frees himself up to desire and fantasise about Mindy with no fear of reprisal. That is, on one level, he no longer has to concern himself with the deterioration of his marriage because of Mindy, but, further, his decision to keep his object of desire at a distance means that he never has to worry about the destructive convergence of his fantasy and reality. By not committing adultery on that one night, Homer frees himself to wander, lust and cheat on Marge every night, in his dreams and unconscious fantasies.

As a final point, I'd look to the scene where Homer and Mindy are eating dinner together at a fancy, romantic Chinese restaurant called Madame Chao's. After dinner, Homer opens a fortune cookie, it read: "You will find happiness with a new love".

This is a notion that Lacan would reject. Rather, we find happiness within our very distance from the objects we believe will make us happy. Desire is a Sisyphean phenomenon where the actual attainment of what we desire is one of life's most morose experiences. That Homer rejects the cookie's advice is telling; we will not find happiness with a new love.

Lacan, J. (1998). The four fundamental concepts of psycho-analysis. London: Vintage.

Whilst the episode's B-Plot sees Bart transition from cool kid to bullied nerd because of some over-zealous private practitioners, the A-Plot of "The Last Temptation of Homer" launches from a safety mishap in the Nuclear Plant. This inciting incident, caused by a masculine disregard for safety protocol, characterises working at the plant as a sort of 'Men's Club'; setting the stage for Mindy Simmon's hiring and her intrusion on the masculine space. Homer, Lenny and Carl gather to lament their incoming castration, fearing that the arrival of a singular female worker will so totally disrupt their workplace atmosphere that certain masculine freedoms will be removed from them (be it taking off their pants, spitting on the floor or peeing in the water fountain). That male anxiety is soon abetted by her seamless integration into the workplace, but whilst the rest of his co-workers move on quick from this new element, Homer is smitten. For him, his encounter with Mindy is a moment of pure desire upon first sight and it is accompanied by humorous hallucinations.

"Hey, Homer, you're hallucinating again!" "Not a good sign."

The hallucinations (and later in the episode, dreams) are important to how the episode communicates Homer's desire for Mindy. It is within them that we see what the objet petit a is: an intangible, extra-natural quality that is the actual point of what we desire. Caviar, for example, is not desirable to us because of its intrinsic qualities, how it looks, how it smells, how it tastes, but is instead only desirable because of the multitudes of meanings that its physical form belies: if you eat caviar, you will have social status, you will be a connoisseur, a person of taste and so on. The objet petit a, though, is an entity that is permanently absent. In Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, when discussing the Freudian character of the butcher's wife, who tells her husband that whilst she loves caviar, he must never buy it for her, Lacan wrote:

“You love mutton stew. You’re not sure you desire it. Take the experience of the beautiful butcher’s wife. She loves caviar, but she doesn’t want any. That’s why she desires it.” (1998: 249)Importantly, the objet petit a does not actually exist. This is why when we finally attain what we desire it loses the metaphysical, theological quality, the objet petit a, which made what we desired desirable in the first place. Homer's hallucinations represent the fantastical excess of the objet petit a: his first feelings of desire towards Mindy are not grounded in material reality, but are rather concerned with such untraceable, intangible qualities.

"Ain't you never seen a naked chick riding a clam before?"

"Think unsexy thoughts. Think unsexy thoughts."

One of the great strengths of this episode is how Mindy is never shown to be some kind of disruptive, evil woman, a seductress with the explicit aim of destroying the nuclear family; she's given a nice bit of humanity. Meanwhile Marge has very little presence in the episode and even in the dream sequence exposing her potential, alternate life as President, she's only heard from off-screen. Unlike an episode like "Colonel Homer" (S3E20), where a conflict between Homer/Marge is clearly apparent, the story here is not a story about how awful Homer's life is and how he needs an outlet to assuage his mid-life crisis, but rather a story that is concerned with those tumultuous, sudden moments of desire that simultaneously manage to feel essential to our being and completely alien from us.

In Lacan's formulation, the act of desire is not a desire for just one thing (be it a person, food or whatever item you may desire), but is always a desire for desire itself. It's a wholesome sight when Homer returns to Marge at the episode's end and the relief an audience feels is made all the more tangible by how close it seemed Homer had come to pursuing a life with Mindy, instead of persisting with his marriage. Yet, can we not say that this was actually the true calamity? In that, were he to pursue his relationship with Mindy, he would realise she lacks that objet petit a and would realise that his fantasy did not exist in reality. That he returned to Marge has meant that, whilst he ostensibly loves his wife, he has also liberated himself to fantasise about Mindy ad infinitum. In this sense, Homer doesn't want what he thinks he wants, rather he wants to sustain the very act of wanting. By returning to Marge, he frees himself up to desire and fantasise about Mindy with no fear of reprisal. That is, on one level, he no longer has to concern himself with the deterioration of his marriage because of Mindy, but, further, his decision to keep his object of desire at a distance means that he never has to worry about the destructive convergence of his fantasy and reality. By not committing adultery on that one night, Homer frees himself to wander, lust and cheat on Marge every night, in his dreams and unconscious fantasies.

As a final point, I'd look to the scene where Homer and Mindy are eating dinner together at a fancy, romantic Chinese restaurant called Madame Chao's. After dinner, Homer opens a fortune cookie, it read: "You will find happiness with a new love".

"Hey, we're out of these "New Love" cookies." "Well, open up the "Stick With Your Wife" barrel."

Lacan, J. (1998). The four fundamental concepts of psycho-analysis. London: Vintage.

Friday, 30 November 2018

The Amber Burning

I don’t know why I’m writing this, anyone who reads this is going to think I’m insane. Maybe I am. Damn it. So I’m just going to write it down. Because if I don’t I’m pretty sure it’s going to violently burst out my head. I need this out my brain.

So, first, I guess I should say writing isn’t my strong suit. I kind of hate it actually. How full of yourself do you have to be to just sit and write? It’s all vile and conceited really, when you get down to it. I like reading though. And I like reading about wizards. Everyone has an opinion on wizards. I don’t care. I like wizards.

I’ve been trying to die since I was 13. But I’ve always been too afraid. And I always found that kind of funny. I don’t want to live, I don’t want to die, I’m caught in some purgatory between them, never really trying too hard at doing either. Anyway, between living and dying, there are a few strange quirks you pick up along the way. When I was 15, long after I had broken a light trying to hang myself with my school tie but not so long after I’d tried cutting myself and got scared from all the blood, I started walking to the train station. One day I was going to throw myself on those tracks. Not in front of a passenger train, but one of those massive freight trains that speed right through the station and look like they couldn’t stop even if they wanted to. But, of course, that’s just a bit too terrifying. A few steps off the platform and I’m gone. I don’t know why being nothing scares me but whatever little, worthless, shit I count for always kept my feet on the station and my head from being turned into bloody pulp.

Still, I started to go to the train station. Every day, eventually. And I’d just stand there, watching the trains rush by. After a few weeks, I started sitting instead. Making judgy comments to myself about the commuters. And then some weeks after that, I started bringing my books. It was Autumn, in the afternoon, and I was sat reading. I’d not looked up at the trains in some time, I was somewhere far, far away from them. But, when I wasn’t looking, a train had pulled in. Off its passengers came, though I saw none of them except for one old man. He sat next to me and I realised something very strange. I’m 19 now. This man must have been in his 70s. Possibly older. But there was a strange kinship between us. Hell, he looked like me. But, with the twisted distortions of time, I realised it was yet another one of the universe’s mockeries. Every facet of my face that I hated, each one that I had pored over with disgust in the mirror, was amplified here tenfold on the face of a haggard, decrepit old man. He was me, if my chin had disappeared far into my neck, if my hair was thin and straggly, grey instead of black, and if my nose had never stopped growing.

We were sat together for a while, I soon returned to the land of wizards (though it had now lost some of its escapist appeal); he just sat. We said nothing to each other. That was until the old man stood up suddenly and, glancing at my book, said, “Do you want to know how it ends?”

I met his eye, looked at him directly and said, “No.”

“Yeah, I never found out either.”

And then he just walked off. But I noticed the train he’d got off was still here. And the carriage door was still open. And I really can’t tell you what was going through my mind in that moment because, for some reason, I jumped on.